Khwaja Ahmed Abbas, better known as KA Abbas was a litterateur, journalist, author, screenwriter, film-maker, and film critic. There were perhaps only a few of the dozen different hats he wore in his lifetime. His body of work remains a testament to this man’s dedication, commitment and perseverance.

|

| Picture courtesy: Wikipedia Commons |

|

|

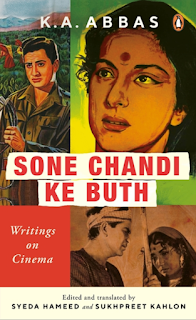

Imprint: (Penguin) Vintage Books Published: Jun/2022 ISBN: 9780670095933 Length : 240 Pages MRP : ₹599.00 |

Divided into three sections - Funn aur Funnkaar, Kahaniyaan, and Articles (including some from The Bombay Chronicle), the raconteur’s pen is gives you a clear view of the glamorous world of films, and the decay under the glitz.

In Funn aur Funnkaar, he takes us behind the screen to reveal his insights into personalities as diverse as V Shantaram and Satyajit Ray; Prithviraj Kapoor and Raj Kapoor; Dilip Kumar and Amitabh Bachchan, Sahir and Meena Kumari.

If he is honest about Dilip Kumar making inane films such as Azaad and Leader despite his immense talent, he is equally honest about the actor asking him why he had made a film as inane as Gyarah Hazaar Ladkiyaan. If he’s admiring about Prithviraj Kapoor’s commitment to the art of acting, he’s equally admiring about Raj Kapoor’s love for cinema while decrying his love of himself. (Though I must confess to enjoying Yasir Abbasi’s translation of this particular chapter better than the one in this book.)

KA Abbas also admits to being thoroughly influenced by V Shantaram, but that does not stop him from ruing that the film-maker had traded his social consciousness for technical wizardry and production gloss in his later films.

His reminiscences of Sahir are of the man, not the poet, but his admiration for Meena Kumari and Balraj Sahni are for their commitment to their profession.

In fact, in his profile of Meena Kumari, he narrates how his heroine (Char Dil Char Rahein) waded through flooded roads to reach the sets on time, and throughout the shooting of the film, remained in character, sitting on the floor on a dhurrie and walking bare feet on hot stones because her character would do so.

He remembers giving Amitabh his first role only after

writing to Harivanshrai Bachchan for permission and talks of how the actor

would always refer to him as ‘Mamujaan’ (uncle) even after he became a

superstar.

The second section, Kahaniyaan, is a set of stories of people from different hierarchies in the film industry. The mother who drugs her child so she can earn enough money to take the child to a doctor; a ‘duplicate’ who dies while performing stunts; an actress whose desire to die far outlives the doctor who’s fighting to keep her alive; another actress whose search for the fountain of youth ends in tragedy… what seeps through the writing is the compassion for their struggles, and the stinging indictment of the industry as one given over to crass commercialism. It was his avowed belief that films needed to have a heart and be a medium of social change. In a story called ‘Actress’ he also castigates himself for falling into the same trap that he despises. To me, this section was the weakest because the stories, while heart-wrenching in essence, didn’t make me feel what the author wanted to convey. Perhaps reading it in the original Urdu may evoke the emotions the stories deserve.

The third and final section is a series of articles that he had written at various times, including those he wrote for the Bombay Chronicle. As a film-maker, writer and critic who watched at least one film a day for over 50 years, he’s uniquely placed to offer his views on what plagues Indian cinema. They include reviews of films, his analysis of what’s wanting in the cinema of the day (and remember, the articles curated for this book were written in the late thirties/early forties) and his views on workman compensation and equity in the industry. (He famously paid his actors and crew the same amount, senior or junior.) It’s a shame that while much has changed, much remains the same.

I have one bone to pick, however: the article where he suggests that films be used to spread ‘Hindustani’ as the ‘national’ language. “Indeed, the considerable resources and influences of the persons and organizations engaged in the work of evolving and spreading the national language,” he wrote, “could be used very effectively to encourage the production of films in Hindustani only, aiming at a gradual elimination of films in provincial languages.”

To me, it’s shocking that someone of the stature of KA Abbas, and someone who loved cinema as much as he did, could express a view that there should be one ‘unifying’ language and that other industries should stop making films in their respective languages. It is even more troubling to read this view in the present climate where a government is set on imposing one religion, one language, one identity on the country. I devoutly hope that in the ensuing four decades, his views had changed.

I did find the writing slightly didactic and wished that the translated articles at least had not stuck so close to the same tone as the articles written in the English of the 40s by the author himself. Still, complemented by photographs from his personal collection and the posters of his films, Sone Chandi ke Buth is a welcome addition to writing on Hindi cinema.

No comments:

Post a Comment