|

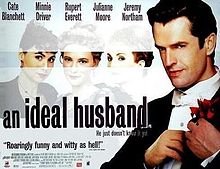

Directed by: Oliver Parker

Starring: Jeremy Northam, Rupert Everett,

Cate Blanchett, Minnie Driver,

Julianna Moore

|

I first saw Rupert Everett in My Best Friend's Wedding. I promptly fell in love with him. He was jaw-droppingly good looking, carried off a swagger without seeming conceited, and most importantly, had a rapier sharp intellect that translated well on screen. In a film where I cared so little whether the heroine won the (insipid) hero or not, it seemed a shame that she didn't seem to notice her much more interesting friend. Of course, he was gay, so that precluded any attraction between them, but I remember thinking - from a straight woman's point of view - 'What a waste of such a good man!' (That reaction only solidified when I later learnt that Everett had come out as a homosexual in real life.)

My husband viewed my transports with amusement. And I looked forward to watching Rupert Everett in any, and all, films I could find, however short his role. When I confess to watching Inspector Gadget and Dunston Checks In (one post, and one pre- the movie I'm reviewing) only so I could watch Rupert Everett on screen - he did the villainous turn so well - it's a measure of how much I liked the actor.

My husband viewed my transports with amusement. And I looked forward to watching Rupert Everett in any, and all, films I could find, however short his role. When I confess to watching Inspector Gadget and Dunston Checks In (one post, and one pre- the movie I'm reviewing) only so I could watch Rupert Everett on screen - he did the villainous turn so well - it's a measure of how much I liked the actor.

So, of course, when An Ideal Husband was released, I had to see it. Especially when it was based on an Oscar Wilde play - one that I had read in college. (The Importance of Being Earnest was a college textbook. I ended up reading the collected works of Oscar Wilde at one sitting.) It was interesting that Everett did not play the 'hero'. It made sense. Lord Goring was definitely the more interesting character. (I am not too fond of the stuffed shirts.)

For those of you who have not read the play, here's a quick run-through...

London. 1895. '...where people are either hunting for husbands... or hiding from them...'

Lord Robert (Jeremy Northam) and Lady Gertrude Chiltern (Cate Blanchett) are entertaining polite society at their home in London's fashionable Grosvenor Square. In admittance are Arthur, Lord Goring (Rupert Everett), a close friend of the Chilterns, Mabel Chiltern (Minnie Driver), the younger sister of Lord Chiltern, and many other friends and acquaintances of the couple. Lord Robert is an upcoming politician, and Lady Gertrude, his supportive and loving wife.

Lord Robert (Jeremy Northam) and Lady Gertrude Chiltern (Cate Blanchett) are entertaining polite society at their home in London's fashionable Grosvenor Square. In admittance are Arthur, Lord Goring (Rupert Everett), a close friend of the Chilterns, Mabel Chiltern (Minnie Driver), the younger sister of Lord Chiltern, and many other friends and acquaintances of the couple. Lord Robert is an upcoming politician, and Lady Gertrude, his supportive and loving wife.

Also present is a Mrs Laura Cheveley (Julianna Moore), a well-born young woman who is welcomed in the finest houses, yet has a reputation of skating along the fringes of polite society. Lady Gertrude has been forced to invite her; she knows Mrs Cheveley from her school days, and the latter was not a particular friend even then.

Mrs Cheveley has an ulterior motive in attending tonight's soiree. She has invested heavily in a (fraudulent) scheme to build a canal in Argentina, and hopes to persuade Lord Robert to lend his support to the scheme in parliament. She has an ace up her sleeve - an indiscreet letter written by a young Lord Robert. He had then been persuaded to sell a Cabinet secret to a Baron Arnheim, a secret that had allowed the unscrupulous Baron to buy stocks in the Suez Canal three days before the British government announced its purchase. The money he received for his 'help' is the foundation of Lord Robert's immense fortune. The late Baron Arnheim was both Mrs Cheveley's mentor and lover, and she hopes to use Lord Robert's letter to him as a lever to obtain his stamp of approval.

Robert has much to lose: his career, his reputation and - his marriage. Gertrude is morally inflexible. She adores her husband, but her adoration is built on her approval of his personal integrity, both as a man and as a politician. She thinks of him as her 'ideal husband' and will certainly not support moral ambiguity. His decisions - both personal and public - must be above reproach. Mrs Cheveley, cognisant of Lady Gertrude's dislike of her, is not above taking a swipe at her; as she leaves their home, she makes a pointed comment about having Lord Robert's support for the Argentinian canal scheme.

Gertrude is shocked, but not knowing what's in store for her husband, she insists that her husband go back on his word. Not being able to confide in her his reasons for giving in to a scheme that he had, thus far, been vociferously against, and forced to live up to her idealistic vision of him, Robert writes to Mrs Cheveley - he cannot, he will not stand in support of the scheme. With that pen stroke, he has sealed his fate. Mrs Cheveley is playing for extremely large stakes here, and she cannot afford to lose.

Robert has much to lose: his career, his reputation and - his marriage. Gertrude is morally inflexible. She adores her husband, but her adoration is built on her approval of his personal integrity, both as a man and as a politician. She thinks of him as her 'ideal husband' and will certainly not support moral ambiguity. His decisions - both personal and public - must be above reproach. Mrs Cheveley, cognisant of Lady Gertrude's dislike of her, is not above taking a swipe at her; as she leaves their home, she makes a pointed comment about having Lord Robert's support for the Argentinian canal scheme.

Gertrude is shocked, but not knowing what's in store for her husband, she insists that her husband go back on his word. Not being able to confide in her his reasons for giving in to a scheme that he had, thus far, been vociferously against, and forced to live up to her idealistic vision of him, Robert writes to Mrs Cheveley - he cannot, he will not stand in support of the scheme. With that pen stroke, he has sealed his fate. Mrs Cheveley is playing for extremely large stakes here, and she cannot afford to lose.

The next evening, Robert confides in his friend. He had helped the Baron make three-quarters of a million pounds; his reward was 110,000 pounds. He went straight into parliament, and his path, since then, has been on the straight and narrow. Arthur asks Robert to confess the whole to Gertrude, but Robert is loath to do so. He hopes Arthur, being her oldest friend, will talk to her.

Arthur meets Gertrude the next morning, and tries to convince her to be more forgiving of human frailty. He cannot bring himself to betray Robert's confidence, however, so his suit doesn't prosper. Finally, he decides to tell a surprised Gertrude to come to him if she's ever in need of any help.

Meanwhile, Mabel walks in, and begins sparring verbally with Lord Goring - this is their usual manner of interaction. Suddenly, however, a tiny vein of seriousness creeps in, surprising both of them.

Mrs Cheveley is hardly likely to let things be - she replies to Lord Robert, quite unexceptionably, though her post script at the end is both a warning and a threat. In a master stroke, she exposes his dark secret to Lady Gertrude. One stone, two birds.

Gertrude cannot bear to think that her husband has feet of clay. His youthful misdemeanour lessens his standing in her eyes, and after a short, sharp argument, a shattered Gertrude asks him to leaves the house. And the marriage.

Arthur is getting ready to escort Mabel to an art gallery when his father, Lord Caversham (John Wood) puts in an appearance. The elderly peer is justifiably incensed at his progeny's lack of interest in marrying (and dutifully presenting him with an heir). He is followed by Robert, who has come to ask for Arthur's advice.

Arthur meets Gertrude the next morning, and tries to convince her to be more forgiving of human frailty. He cannot bring himself to betray Robert's confidence, however, so his suit doesn't prosper. Finally, he decides to tell a surprised Gertrude to come to him if she's ever in need of any help.

Meanwhile, Mabel walks in, and begins sparring verbally with Lord Goring - this is their usual manner of interaction. Suddenly, however, a tiny vein of seriousness creeps in, surprising both of them.

Mrs Cheveley is hardly likely to let things be - she replies to Lord Robert, quite unexceptionably, though her post script at the end is both a warning and a threat. In a master stroke, she exposes his dark secret to Lady Gertrude. One stone, two birds.

Gertrude cannot bear to think that her husband has feet of clay. His youthful misdemeanour lessens his standing in her eyes, and after a short, sharp argument, a shattered Gertrude asks him to leaves the house. And the marriage.

Arthur is getting ready to escort Mabel to an art gallery when his father, Lord Caversham (John Wood) puts in an appearance. The elderly peer is justifiably incensed at his progeny's lack of interest in marrying (and dutifully presenting him with an heir). He is followed by Robert, who has come to ask for Arthur's advice.

It appears that Lord Goring is to be inundated with visitors that day, even if, as he undutifully tells his father, "I never receive visitors on Thursdays, between seven and nine in the evening." He also receives a hand-delivered letter - written on pink note paper - from a distraught Gertrude, who's taking him up on his earlier offer to stand her friend through thick and thin. She is coming to him now to seek his advice, she writes. But Arthur has yet another - unexpected - visitor.

Lord Goring's butler, mistaking her for the woman whom his master was expecting, shows her into the drawing room, where she spots Lady Gertrude's letter. Not exactly known for her propriety, she reads it with great interest - and purloins it.

Arthur, assuming that it is Gertrude in the drawing room, opens the connecting door between his study and the drawing room - in the hope that when Gertrude hears her husband's regrets, she will forgive him.

Unfortunately, Robert, hearing a chair creak in the adjoining room, throws open the doors, and mistakenly supposes that his friend and his arch enemy are complicit in the plan to ruin him. A stunned Arthur can offer no explanations, and after accusing him of duplicity, Robert storms out of the house.

Meanwhile, an unabashed Mrs Cheveley has a proposal for Lord Goring. She still loves him, and if he will marry her, she will hand over the letter that can save his friend from ruin.

Lord Goring's butler, mistaking her for the woman whom his master was expecting, shows her into the drawing room, where she spots Lady Gertrude's letter. Not exactly known for her propriety, she reads it with great interest - and purloins it.

Arthur, assuming that it is Gertrude in the drawing room, opens the connecting door between his study and the drawing room - in the hope that when Gertrude hears her husband's regrets, she will forgive him.

Unfortunately, Robert, hearing a chair creak in the adjoining room, throws open the doors, and mistakenly supposes that his friend and his arch enemy are complicit in the plan to ruin him. A stunned Arthur can offer no explanations, and after accusing him of duplicity, Robert storms out of the house.

Meanwhile, an unabashed Mrs Cheveley has a proposal for Lord Goring. She still loves him, and if he will marry her, she will hand over the letter that can save his friend from ruin.

Will Arthur, Lord Goring succumb? Will he marry a woman he doesn't love in order to save a friend who now hates him? Does Mrs Cheveley really love Lord Goring? Will Lord and Lady Chiltern manage to sort out their marital troubles after all? And what about poor Mabel Chiltern who is in love with Lord Goring, and is waiting for him?

At 10.30 that night, the fates of all these people will be decided. Or does Mrs Cheveley still hold a hidden ace?

Oscar Wilde is always good fun. (Do read the original play for the dialogues.) Not the 'he slipped on a banana peel' sort of situational laughter, but the sly, satirical humour that peels off the façade of polite society in the Victorian era. Unlike the bleakness that underlined the works of his contemporaries (Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, George Eliot et al), Wilde used humour to skewer the upper classes. His sarcastic, often biting wit, found an outlet in his plays, of which The Importance of Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband are perhaps the most famous. It is not clear whether he wrote the latter as expatiation of his 'sins' or as a confession of his affair with Lord Alfred Douglas. Certainly, he makes a push for forgiveness in the play - No one should be judged entirely on misdeeds of their past - and stresses the need to not ruin lives that are of great value to society because of supposed 'sins'.

An Ideal Husband is a morality play of sorts, leavened by wit and humour. The play, as published, was not the one originally staged, since Oscar Wilde deleted many scenes, and added others. However, he was arrested for 'indecent behaviour' in the middle of the staging, and credit for authorship was taken away from him, even though the play continued to be staged.

At 10.30 that night, the fates of all these people will be decided. Or does Mrs Cheveley still hold a hidden ace?

Oscar Wilde is always good fun. (Do read the original play for the dialogues.) Not the 'he slipped on a banana peel' sort of situational laughter, but the sly, satirical humour that peels off the façade of polite society in the Victorian era. Unlike the bleakness that underlined the works of his contemporaries (Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, George Eliot et al), Wilde used humour to skewer the upper classes. His sarcastic, often biting wit, found an outlet in his plays, of which The Importance of Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband are perhaps the most famous. It is not clear whether he wrote the latter as expatiation of his 'sins' or as a confession of his affair with Lord Alfred Douglas. Certainly, he makes a push for forgiveness in the play - No one should be judged entirely on misdeeds of their past - and stresses the need to not ruin lives that are of great value to society because of supposed 'sins'.

An Ideal Husband is a morality play of sorts, leavened by wit and humour. The play, as published, was not the one originally staged, since Oscar Wilde deleted many scenes, and added others. However, he was arrested for 'indecent behaviour' in the middle of the staging, and credit for authorship was taken away from him, even though the play continued to be staged.

Like many of Wilde's plays, this comedy of manners hinges on misunderstandings. It works, as all good plays do, not because of the plot itself (which turns quite complicated), but because the actors do a fantastic job of making their lies and cheating and blackmail plausible.

What I liked about the character (and the way Northam played him) is that he is not a callow youth led astray by an older, experienced man. Well, he is, in a way, but he is not naïve. "You didn't know what it was to be poor," he tells Goring, "You didn't have ambition." It is that ambition that Baron Arnheim harnesses, and it is quite clear that Chiltern has no regrets. What he does have, instead, is fear. Of losing his wife's love, of losing the career that he's worked so hard for, of losing the respect of his peers who now elevate him to plaudits.

I love Cate Blanchett. She is an actress from whom I expect nothing less than a wonderful performance, and I took it almost as a personal insult that the Academy Award went to Gwyneth Paltrow for Shakespeare in Love when Blanchett was in the running for Elizabeth. (I personally thought that Paltrow's thank you speech while receiving the Oscar was worthier of the award than her performance as Viola De Lesseps in the movie.) Here, Blanchett plays Lady Gertrude with a vulnerability that underlies her strength.

She is the strength behind her husband, motivating him to do more than just remain a peer of the realm. She is educated, liberal, politically conscious, and unable to forgive her husband for a perceived flaw, never mind that it occurred in his youth. Cate Blanchett straddles the line between being a rigid, inflexible smug prude, and a vulnerable, loving wife with consummate ease.

Rupert Everett. He is the reason I watched this film again. He is Arthur, Lord Goring - according to literary critics, Wilde's alter ego - 'the idlest man in London'. Lord Goring is the objective observer, the character who, though a part of the ensemble, can still remain detached and removed from the action. Everett plays him well - the slightly dandified gentleman who is the deux ex machina who saves the day in the end. Everett was charming, laid-back, flirtatious, amused - a social butterfly, who really doesn't seem to care too much about anything. Yet it is he, who as Lord Goring, famously proclaims “I only talk seriously on the first Tuesday of each month… between noon and three,” who is cast into the role of saviour. The irony is delicious, and no one appreciates it as much as Lord Goring himself.

Everett, as Goring, gets all the best lines in the play, and he says them charmingly, gently, ruefully, making it appear like part of everyday conversation, instead of tossing a series of one-liners at the audience. 'Do you always understand what you say?' asks Lord Caversham, to which he replies, 'Yes, if I listen attentively.'

The situation in which he finds himself amuses him no end (even if he has a moment of fright), and nowhere is it more visible than in the scene where he tries, desperately, to keep all the people who converge on his home separate from each other, even as he realises that his erstwhile fiancée has very neatly laid a trap for him. An Ideal Husband is his movie, and the director gives him enough room to be both subtle and scathing - and incredibly charismatic.

Among the three woman characters, it is Mrs Cheveley who has the most agency. She is charmingly vicious, ready to stoop to any level to attain her ends. Julianna Moore is a fabulous actor, and she chews on her part with relish. She is the calculating, scheming Mrs Cheveley to the T. Her smile is both devilish and disarming, and she's the very image of calculated wickedness. Her Mrs Cheveley could be the mirror image of Arthur, Lord Goring. They are both Machiavellian, both able to scheme and conspire and plot.

Among the three woman characters, it is Mrs Cheveley who has the most agency. She is charmingly vicious, ready to stoop to any level to attain her ends. Julianna Moore is a fabulous actor, and she chews on her part with relish. She is the calculating, scheming Mrs Cheveley to the T. Her smile is both devilish and disarming, and she's the very image of calculated wickedness. Her Mrs Cheveley could be the mirror image of Arthur, Lord Goring. They are both Machiavellian, both able to scheme and conspire and plot.

Parker's adaptation is quite good, though he faced criticism for 'modernising' some of the dialogue. I did not mind him focusing more on the main characters, deleting a couple of the minor ones. My peeve with him is that he removed the context of the play, erasing its importance, and so, some of the lines fall flat. But where he diverged completely from the play (he uses a counter offer instead of a misplaced diamond bracelet), he made it both plausible and possible - Mrs Cheveley is a gambler at heart. Parker did have a master's script to fall back upon. Oscar Wilde's lines make us laugh, then ponder, then laugh some more. And when we aren't laughing, we are smiling - with sympathy and empathy. Clothed in wit and biting humour, the play is, after all, both a social satire and a comedy of manners.

No comments:

Post a Comment