I have never been a great fan of Asha Parekh. I mean,

she was pleasant enough, and starred in some rather decent 60s entertainers,

traipsing over hill and vale, romancing some of the biggest heroes of her time,

getting to lip sync to some memorable songs... I did enjoy her presence when I watched these films. However, I didn't miss her when

she wasn't on screen, nor did I watch a contemporary actress and sigh, 'I wish

Asha Parekh had done this role.' She was, well, rather bland – in my opinion – and I

could take her or leave her without overthinking the issue.

So, on a recent sojourn to India, when I was buying my

usual quota of books – I brought back a whole suitcase of them – I dithered

over buying her autobiography. Was I really interested enough to want to know

more about her? I wasn't sure. Yet, she was one of the most successful

actresses of her time, responsible for many pleasant hours I spent at the cinema, and

what's one more book, after all? Even if it had a rather weird title? I

succumbed to temptation and bought it.

Was it worth it?

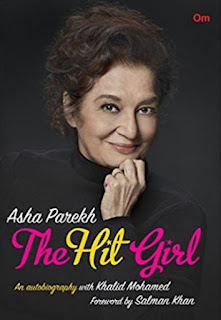

The Hit Girl, co-authored with veteran journalist-screenwriter-filmmaker Khalid Mohammed, is a look back at the veteran actress's life and career.

|

Om Books International

264 Pages

ISBN: 978-9386316981

Rs895 |

Interestingly, the cover features the actress as she

is today. 'Interestingly' because, typically, autobiographies feature the

authors at their most presentable - which, in the case of actors, is usually a

portrait of their younger selves. The book begins with a foreword by Salman Khan. While he rambles on at length, the tone is rather generic, and despite her

closeness to the Khan family, a question arises – why Salman?

The foreword is followed by a long (very long)

'Author's Notes', and essays by directors Sanjay Leela Bhansali and Sai

Paranjpye – neither of whom have worked with Asha Parekh. While Bhansali's five-page

essay extolls her as 'born to be my heroine', Paranjpye's equally long essay

titled 'Personally Speaking' talks about her interactions with the actress in

Asha's capacity as CBFC chairman. It is not that the essays are tedious, but

neither are they particularly interesting. By this time, I'm wondering whether

I'm ever going to hear Asha's own voice.

However, once I waded grimly through the first 40 pages,

the real story began.

Asha Parekh begins with the story of her parents'

inter-religious wedding which cut them off from both their families for a period of

time. She then goes on to chronicle her life and times as an actress, dancer,

philanthropist, and television producer.

She narrates how she loved to dance and was not loth

to do so at any given occasion. A dance performance attended by Bimal Roy led to the offer of a bit role in Maa (1952). A few years later, her

dancing skills gave her the chance to perform alongside Vyjayanthimala in a

dance sequence for Asha (1957). She speaks glowingly of the senior

actress who helped her when she faltered.

Her first big break was Goonj Uthi Shehnai

(1959) opposite Rajendra Kumar. Unfortunately, she was dropped after a few days'

shooting – the director felt she was not 'heroine material'. Moreover, Ameeta,

fresh from the success of Tumsa Nahin Dekha (1957) slashed her price in

half. This rejection was a setback in more ways than one – committed to

Vijay Bhatt for Goonj Uthi Shehnai meant that she lost out on signing a three-film

contract with V Shantaram's Rajkamal Studios.

|

| With Rajendra Kumar in Goonj Uthi Shehnai |

Sasadhar Mukherjee encouraged her to join

Filmalaya's acting school. (There, Asha would meet another debutante waiting in the wings – Sadhana – who would one

day become one of her closest friends.) Dil Deke Dekho (1959), her

first full-fledged role as heroine, would not have happened but for a quirk of

fate: RK Nayyar, who had become besotted with Sadhana, requested that he be the

one to introduce the debutante in Love in Simla. This left Nasir Hussain with

Asha Parekh, a professional relationship that kick started her career and

morphed into something more serious.

Asha is honest in her acknowledgement of Sadhana’s

versatility, preferring to see herself as the bubbly ingénue who could dance.

There was no professional rivalry between them, nor with Saira Banu, who made an equally successful debut a couple of years later. That honesty is

evident throughout the book, especially in her assessment of herself as a performer: she was ‘not likely to be the prime

candidate for parts requiring implosive, soul-searching performances’ (Pg. 106), she says. She had refused Ismail Merchant’s The Householder (1963) because she was not

confident of art-house cinema. There’s a twinge of regret – had she accepted the role, she may have evolved as an artiste.

However, she was now an extremely successful actress,

and she gracefully acknowledges the directors who mentored and made her the

actress she was – Nasir Hussain, Raj Khosla, Vijay Anand, Shakti Samanta,

amongst others. Her reminiscences about her heroes are equally refreshing:

How Dev Anand was an enthusiastic, disciplined costar but kept to

himself after the shooting was over.

How Shammi Kapoor taught her to lip sync to songs and

Geeta Bali helped with her makeup. (The latter even wanted Asha to call her ‘chachi’ (aunt) – which she did, though she baulked at calling her hero, ‘chacha’.)

How Sunil Dutt was shy and couldn’t bring himself to

embrace her for a scene in front of her mother.

How Rajendranath once sent her flowers along with a

card saying ‘Mujhe dil deke dekhoji.'

How Guru Dutt

refused to talk to her unless she gave him one box of cashew nuts.

How Bharat Bhushan (and

Hrishikesh Mukherjee) weaned her off Mills & Boons and influenced her

reading.

How Rajesh Khanna

was anything but arrogant and difficult.

How Shashi Kapoor

once fooled her into believing he was a woman.

There are some other interesting tidbits:

How Asha was often seemingly 'possessed' by the spirit

of a woodcutter’s wife, and still believes in rebirth.

How she was a tomboy right through her childhood, and

saw her role in Ziddi (1964) as an extension

of herself.

How Premnath spotted her dancing and insisted on her

performing for Madhubala, Nimmi, and his wife, Bina Rai, proclaiming that she

was ‘born to dance’.

How her real name could have been Zulekha or Gangubai, and,

if left to Dilip Kumar, her reel name may have been Asha 'Pari'.

There are a few regrets, both personal and

professional – of falling in love with Nasir Hussain but not wanting

to break up his marriage or be the other woman.

Of not being able to work with Satyajit Ray who wanted to cast

her in Kanchenjunga, due to a paucity

of dates.

Of missing out on opportunities to work with Raj

Kapoor, Dilip Kumar, and K Asif.

Of foolishly refusing Aradhana.

Asha slides over controversies – of allegedly

passing an uncomplimentary remark about Dilip Kumar.

Of being accused of deleting Simi Garewal’s scenes in Do Badan, Laxmi Chhaya’s role in Mera Gaon Mera Desh, and Aruna Irani’s

role in Caravan.

Of refusing a film opposite Amitabh Bachchan because

he wasn’t a big star.

Of a long-standing feud with Shatrughan Sinha.

Of having begged a politician for a Padma Bhushan.

No book about Asha Parekh would be complete without a mention of her dancing – a whole chapter is devoted to her training in Kathak and Bharatnatyam, and her successful dance tours across the country and abroad. She also talks about her foray into Gujarati films and other regional cinema, as well as her stint as a television producer and CBFC chief.

No book about Asha Parekh would be complete without a mention of her dancing – a whole chapter is devoted to her training in Kathak and Bharatnatyam, and her successful dance tours across the country and abroad. She also talks about her foray into Gujarati films and other regional cinema, as well as her stint as a television producer and CBFC chief.

Asha writes honestly about her

disenchantment with the marginalised ‘mummy-ji’ roles she was being offered,

her bouts of depression after the deaths of her parents, and her interest in

social causes. She speaks warmly of her best friends – Waheeda Rehman, Shammi, Helen, Saira Banu, the late Sadhana and Nanda. It is a life well lived, and she does come across as someone who

has no major regrets, not even about her ‘single’ status.

All good.

So why did I feel dissatisfied

when I finished the book? Yes, the book could have done with the services of a

good editor – there are a couple of jumps in the narrative that are discordant. But that's not the reason. Mohammed is a veteran journalist and writes well. That's not it, either. Perhaps it is the sanitised feel of the narrative. Perhaps Asha

Parekh did not want any more controversies. Perhaps she felt the need

to play safe. Whatever the reason, the book presents but a superficial view of

an actress who was once considered a style icon and a lucky mascot.

She

deserved better, and so did we.

The Hit Girl by Asha Parekh

The Hit Girl by Asha Parekh

No comments:

Post a Comment