|

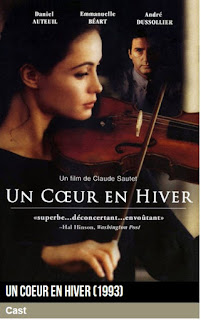

A Heart in Winter

Directed by Claude Sautet

Music: Maurice Ravel

Starring: Daniel Auteuil, Emmanuelle Béart,

André Dussollier, Brigitte Catillon,

Élizabeth Bourgine

|

I

fell in love with Emmanuelle Béart when I first saw her in Un Cœur en Hiver

in the time of VHS tapes. Daniel Auteuil has been a favourite forever, and I’ve

been wanting to review this film ever since. It’s only recently that Netflix

made the film available on DVD, and I settled down for a re-watch. I was

curious to see how I would feel about the film nearly 20 years since I first

watched it. More about that later.

Un Cœur en Hiver begins

with Stéphane’s voiceover – he runs the studio for Maxime (André Dussollier),

who takes care of the commercial aspects of the business, including customer

relations. Maxime, says Stéphane, likes to win, and he, Stéphane, doesn’t mind

losing. Stéphane is happy with his work, and lives vicariously through Maxime. Stéphane

is happy being in the background, and is happier still to immerse himself in

the world of music. When he’s not repairing or building violins, he’s

listening to the rehearsals or concerts of his clients. Maxime, on the other

hand, is a world traveller, lover and liver of the good life. He’s married, but

his marriage has settled into boredom, to mitigate which he indulges in transient relationships. The understanding between the two men is such that

they don’t need words to communicate. It’s a match made in heaven.

Until,

one day, Maxime takes Stéphane out to lunch. He has something very important to

say. “What’s it?” asks Stéphane, completely deadpan. “I’ll tell you when you

wipe that grin off your face,” says Maxime. “It’s gone,” says Stéphane, without

moving a muscle. From the conversation that follows, we learn that Maxime has

fallen in love. The woman in question is Camille (Emmanuelle Béart), a rising

concert violinist.

So

much in love, in fact, that he’s asked his wife for a divorce. What’s more,

he’s rented an apartment nearby which he’s having done up, so he can move in

with Camille. Stéphane is surprised – Maxime almost always tells him of his

affairs. Why has been so silent for so long? Because of his concern for

Camille, says Maxime. Camille is understandably nervous about their

relationship, feeling it’s been moving too quickly, and Maxime doesn’t want to

impose upon her. Besides, Camille is devoted to her art, and Maxime wants her

career to flourish.

So

when is he going to meet her, asks Stéphane. ‘’Look straight ahead,” says

Maxime. Camille is having lunch with her agent, Régine (Brigitte Catillon) a

couple of tables away.

Sensing Stéphane’s look, Camille casts an interested

glance their way. On their way out, Maxime joins the two women. It’s clear to Stéphane

that he dotes on Camille.

Now

that Maxime has ‘introduced’ her to Stéphane, so to speak, he brings her around

more often. Stéphane doesn’t have much to say, really, but his very quietness

intrigues Camille. Stéphane, too, is more interested than he lets on.

When he

visits his old teacher, Lachaume (Maurice Garrell) he asks him about Camille.

She had been his student just as Stéphane and Maxime had once been. Lachaume

speaks highly of her; he remembers her as a ‘smooth, hard girl’ who kept to

herself, but remarks that beneath her discipline, she had a temper.

Meanwhile,

Camille comes to the shop with Régine, because her violin has been giving her

trouble. She plays for Stéphane, and the latter is quick to spot the problem.

Camille leaves her violin behind so Stéphane can fix the defect, but reminds

him that she needs it for a professional recording on Friday. Stéphane promises

to have it ready. During

the recording, however, Camille is distracted.

She knows she’s slowing down the

movement. Stéphane, who’s in the audience, quietly gets up and leaves.

Stéphane’s

only real friend is Hélène (Élizabeth Bourgine), who owns a bookstore. She

understands him. It is to her that Stéphane mentions his complicated

relationship with Camille. Attraction is too strong a word, and Stéphane

doesn’t believe in love. And it seems to him that love is everywhere, even in

cookbooks. “Do you find that obscene?” asks Hélène. No, replies Stéphane. “The

literary description of love is often very beautiful.” But he’s sure that

Camille hates him. Hélène smiles – she’s sure Stéphane enjoys it.

When

he next meets Camille, it’s at a dinner at Lachaume’s house. There’s a heated

discussion about what constitutes art and who gets to decide what art really

is. Stéphane, as is his wont, doesn’t participate. When pressed by Camille to

give his opinion, he admits that both sides have valid points. ‘So we cancel

each other?’ asks Camille. Stéphane shrugs. Lachaume is amused. What Stéphane

means, he points out, is that they might as well shut up. Stéphane agrees that

that is a tempting thought. Annoyed, Camille snaps that they run the risk of

being wrong by speaking up; by keeping quiet, Stéphane can appear to be

intelligent. “Perhaps I’m just afraid,” demurs Stéphane.

The

next day, Camille stops by the shop to pick Maxime up. Maxime, in the middle of

a lucrative deal, excuses himself to talk to the client. At a loose end,

Camille wanders over to where Stéphane is supervising his assistant, Brise

(Stanislas Carré de Malberg). She watches him intently without him noticing

her.

When

Stéphane looks up to see Camille, he’s pleasantly surprised. He offers her a

drink where Camille, uncharacteristically for her, opens up about her

relationship with Régine, who has been consequential in furthering her career.

Yet, she’s beginning to feel suffocated by her mentor. Stéphane offers her an

armchair psychoanalysis. Maxime is glad to see Stéphane and Camille get along.

Hélène,

whom Stéphane meets for lunch the next afternoon, wants to know if Stéphane is

in love with Camille. Though hesitant, Stéphane is unequivocal in his denial.

Hélène pokes further – Camille is in love with Maxime, after all, isn’t she?

Well, yes, concurs, Stéphane, though he had the impression that Camille would

have preferred to dine with him the previous night.

Perhaps

it is this feeling that prompts Stéphane to beat Maxime at racquet ball the

next day. For a change, he’s the victor, and Maxime, who’s leaving for London

that day, is amused. He’ll let Stéphane savour his victory, he smiles. On a

whim, Stéphane visits Camille at her rehearsals and invites her to lunch.

Surprised, Camille agrees and they spend a pleasant hour talking. Camille makes

her interest in Stéphane quite clear.

But

Stéphane seems to have gone back into his shell. He begins to avoid Camille,

and when she finally gets him on the phone, he’s quick to tell her that he’s

busy. His avoidance disturbs Camille, and begins to affect her performances.

Meanwhile,

Maxime has returned from London. He whisks Stéphane off to show him the new

apartment. It’s clear that Stéphane is disturbed at the thought of Maxime

sharing the apartment with Camille. And Maxime begins to suspect that Stéphane’s

feelings for Camille are deeper than even he will admit.

It’s

a suspicion that is soon to be confirmed – following a chance meeting with Stéphane

at a restaurant, Camille confesses to Maxime that she loves Stéphane. Though

hurt, Maxime withdraws with grace.

Will

Camille get the happy ending she craves? Will Stéphane admit, even to himself,

that Camille has become very important to his happiness? What will happen to Stéphane’s

partnership with Maxime?

On

the face of it, Un Cœur en Hiver is the usual love story, a romantic

triangle between one woman and two men. Does it resolve and end in ‘happy every

after’? Certainly, a more usual film might have done so. But as Roger Ebert

points out, “…characters in French films seem more grownup than those in

American films. They do not consider love and sex as a teenager might, as

prizes in life. Instead, they are challenges and responsibilities, not always

to be embraced.”

Claude

Sautet tells the story of these three lovers, painting muddled emotions with

delicacy. Love in Un Cœur en Hiver is as messy as it often is, in real

life. The characters all do things they regret, and there are no do-overs.

Second chances may not always be there, and if they are, one might not always

want to take them. Love can be incomplete.

Stéphane

is a man who cannot love, at least not as most people would define ‘love’. When

Camille asks him whether he’s staying away from her because Maxime is a friend,

Stéphane remarks that Maxime is his partner, not a friend. Camille is surprised

– Maxime considers Stéphane a friend. That’s his problem, responds Stéphane.

Auteuil has a very mobile face, but in this film, there’s a stillness about it

that’s deceptive. As Stéphane, he’s visibly awkward in social situations, and

his natural reserve underlines his inability to commit to intimacy in a

relationship. The damage that he inflicts on Camille is not deliberate; the

lack of an emotional core does not allow him to feel the intensity of her

emotions, or to even understand them. It’s an inward-looking performance and

Auteuil plays him with pinpoint accuracy. Any less emotion and he might have

come across as wooden. Any more, and the character would have tipped over into

a cad.

But

the performance that stood out for me was that of Emmanuelle Béart’s. She

puts in a bravura performance as Camille, a woman who falls in love with a man

she cannot have. What’s even more impressive is that Béart practiced the violin

for nearly a year so she could look authentic playing Ravel’s sonatas on

screen.

Like

Auteuil, Béart has a tough line to straddle – a woman who falls in love with

her lover’s friend is not usually a very sympathetic character. Béart's beauty only adds to her performance as the rigidly controlled Camille. So, when, in one shot, she stoops to a

very public recrimination of Stéphane, almost unhinged in her emotional devastation, the deliberate sloppiness of her very garish makeup is doubly disturbing.

In Béart’s capable hands, the scene becomes poignant rather than overly melodramatic. In

the film’s final shot, Camille turns to look at Stéphane through the car

window. They have made their peace with each other. It’s good-bye.

It’s a shot

that has haunted me ever since I watched this film the first time. It’s the

only time I’ve seen someone’s heart in their eyes.

No comments:

Post a Comment